{[[' ']]}

']]}

Although programming for PSIFF has in the past been criticized by some for consisting of middling titles that coddle their senior demographic—calling into question the responsibility of programmers to educate rather than appease; in other words, to curate rather than program—I'm fully aware that film festival personnel must cater to multiple stakeholders invested in such events, no less the buying public. True to Janus, they must look to the newly introduced as well as the consensually-annointed, to the spectacular as well as the humble, to narratives of all scale and tempo and length, in order to offer a representation of world cinema at this contemporary moment. Some titles will always be missing from such a representation, just as several wait to be discovered, and all in all—with a little thoughtful research beforehand—a good time is all but assured. Then again, as was explained to me by one elderly woman, one can arrange their schedule solely by time slot, like playing scratchers in the lottery. Not my style, but to each their own jackpot.

Perhaps the most notable distinction of this festival from years past, however, was the seeming decrease in talent accompanying their films. I'm not talking about PSIFF's "other" film festival with its red carpet posturing and gala award extravaganzas (which require a separate press pass altogether, let alone a healthy obsession with Hollywood's celebrated marketability), but all those foreign directors with little or no celebrity who in the past have shown up at PSIFF to lobby for their films' chances in the race for the Best Foreign Language film at the Oscars®. With the short list being announced earlier than years past, those no longer eligible perhaps lost incentive to attend? Rumors were circulating widely regarding how the festival would compensate. Will the festival shift to December to anticipate Oscar® pronouncements? Would it re-strategize its Awards Buzz profile and aim for late January? Attendees, such as myself, who schedule PSIFF as a post-Christmas event in a serious effort to get away from winter climates back East, in the Midwest and the Northwest, would suffer not to have our holiday from inclement weather; though, admittedly, this edition of PSIFF disappointed many of us with increasingly chilly weather as the festival progressed and the potential hazard of being hit over the head with a serrated palm frond blown off an overhanging tree.

Bundled up more than usual and dodging such hazards, I managed to catch 25 titles in-cinema, a few on screener, one on streaming while waiting for my flight home in the airport, and arranged for a few substantive interviews (to follow). For now, here's my wrap-up of PSIFF's 24th edition, organized alphabetically.

* * *

Much has been written about Michel Franco's After Lucia (Después de Lucía, 2012) with regard to its scathing indictment of peer bullying, and there's certainly enough of that on screen to make you furious; but, what seemed more interesting to me was the very question asked by many of the audience members as they were leaving the theater: "Why did Alejandra (Tessa Ia) allow herself to be bullied so severely by her classmates? Why didn't she tell her father or anyone in authority? Why didn't she fight back?" The title implies the answer to those queries. Lucia, Alejandra's mother, has died in an automobile accident before the film has even started. Her absence is structural and within it smolders enough survivor's guilt to more than incapacitate any individual, let alone a young teenage girl. I appreciate that Franco has approached the self-inflicted damage of survivor's guilt with such a dry eye; but, even without manipulative music to cue emotion—and similar to his earlier film Daniel & Ana (which I didn't much care for)—Franco ruthlessly exploits the foibles of upper class Mexicans, almost to a fault. Official site. IMDb. Wikipedia.

Winner of the Best Director Prize, as well as Best German Film, at last year's Berlin Film Festival, and the opening night film at San Francisco's Berlin & Beyond, Christian Petzold's Barbara (2012) is anchored on an amazingly restrained performance by Petzold's muse Nina Hoss in the title role. Rivaling Isabelle Huppert in conveying volumes with the slightest arch of an eyebrow—or, more specifically, the creased dimple at the edge of her mouth—I couldn't take my eyes off Hoss for fear of allowing a universe of emotion to pass me by. But this is not merely a performance-driven film; its elegant, precise, nearly classic narrative depicts life under Stasi surveillance, accounting for why Barbara hides so much and reveals so little. And it squares off to Freedom's complicated countenance. Shall Barbara flee to the West with a man who would make her his wife and disallow her to practice medicine? Or should she be the doctor she has trained to be, albeit under surveillance? Official site [German]. IMDb. Wikipedia.

When Cristian Mungiu's Beyond the Hills (Dupa dealuri, 2012) was introduced to its PSIFF audience, the sponsor Lesbian News was resoundly thanked. Spoilers anyone? Of course, the film is accomplished beyond its own narrative, which as a gay male is one I've long endured: the role of the Catholic church and internalized homophobia in misinterpreting and misshaping the very natural feelings between same-sex couples. This is a sad story brilliantly told and its final scenes are as bleak as they are accurate. Official site [Hungarian]. IMDb. Wikipedia.

I'm grateful to Linda Blackaby and Michael Hawley for steering me towards Canadian entry Camion (2012), Rafaël Ouellet's solid drama about a father who—after a fatal vehicle collision (which made me yelp out loud)—suffers a breakdown requiring the assistance of his two sons who come home to help him get back on his feet. By doing so, they move their own lives along towards more authenticity and fulfillment. The performances are all downplayed and honest, you care about these people, and you gain a real sense of homecoming as a resuscitative act. The film's hunting sequence is about as intense and thrilling a turn as in the more visible The Hunt. Men and their guns. IMDb. Facebook.

Winner of the Special Jury Prize, Un Certain Regard, Cannes, Aida Begic's Children of Sarajevo (Djeca, 2012) had its U.S. premiere at PSIFF. I was quite fond of Begic's Snow when it screened at the 2009 PSIFF and was looking forward to Begic's follow-up, which proved not quite as poetic as Snow but commendable nonetheless for Marija Pikic's lead performance as the beleaguered Rahima (earning her the Best Actress award at the Sarajevo Film Festival). The film's narrative is slight—basically the problems Rahima encounters making ends meet while taking care of a delinquent brother who is being bullied at school—but works as a portrait of postwar Sarajevo and the lingering inequities towards Muslims. Having lost her parents to the war, and one brother to drugs, Rahima struggles to keep her youngest brother Nedim on track. Perhaps if she would not wear a head scarf she would not draw provocation upon herself? But Rahima refuses to compromise her integrity.

There were two scenes that harkened back to the beauty witnessed in Snow. Comfortable with a friend, Rahima removes her headscarf and her beautiful hair falls loose like soft water. It suggests how she must guard her beauty, hide it even, within an environment of corrupt politicians and predatorial criminals. Then there is the dream where, with her beautiful hair down her back, Rahima silently pursues a woman dressed in a sky blue burka who moves through war-ravaged Sarajevo. When Rahima finally catches up to her, and the woman turns, for a moment you see that her face is a mirror. As noted in PSIFF's capsule, "Aida Begic's underlying theme is Bosnia's lost moral compass as it remains trapped in a torturously slow transition from a state of war." However, as much as I was invested in the actors' performances of their characters, the narrative lacked traction. IMDb. Wikipedia.

Brazil's feted feature The Clown (O Palhaço, 2011) by Selton Mello presents its charm in straightforward, broad if familiar strokes. Nothing too complex here, hazardously simplistic in fact, but colorfully filmed (and one of only three titles I saw on 35mm at PSIFF) with a palatable moral: cats drink milk, mice eat cheese, and we should all do what we can do. Take it or leave it. Offical website [Portuguese]. IMDb. Wikipedia.

It never ceases to amaze me how powerful Isabelle Huppert is as an actress; how little she has to do to convey so much. In Marco Bellochio's Dormant Beauty (Bella addormentata, 2012), there's a scene where she's in the dark and glances sideways that wowed me. I'm fond of Bellochio's work, caught several of his films at SF's New Italian Cinema years back and had the opportunity to meet him; but, it was Huppert who lured me into this film. I'd give anything to meet her.

Dormant Beauty broaches the important subject of euthanasia against a highly-publicized incidence in Italy that divided the nation. Despite some masterful and truly intriguing editing choices, I found the film "outsized" (as Michael Hawley put it), encouraging melodramatics that perhaps suit an Italian temperament, but not mine. I spent several sessions at the Hemlock Society back in the mid-'90s when a friend of mine dying of AIDS asked me to help him end his suffering by a lethal injection. At that time, I spoke with many individuals who were either wishing to die or asking their loved ones to help them die and never personally experienced the histrionics on display in Dormant Beauty. Instead, I encountered thoughtful individuals who felt no need to heighten the drama of their situations. The choices they were facing had, perhaps, defused their anger, their fear, their uncertainty. I'll never forget those conversations, which convinced me I could not assist my friend (something over which to this day I feel some regret and guilt). But not enough guilt to quote Lady Macbeth in my sleep; a truly "outsized" moment in the film, even for Huppert. IMDb. Wikipedia.

Watching Everardo González's Drought (Cuates de Australia, 2011) was as much an exercise in appreciating González's precise and compassionate eye detailing the hard lives of rancheros living in the water-forsaken regions of northern Mexico as it was putting up with clucking Palm Springs matrons who behave like those folks in Catholic legends who look down from Heaven on those damned in Hell as a measure of their own righteousness. They're more concerned that a burro is hit with a switch than the fact that mothers must worry that their unborn children are malnourished and dehydrated in the womb. They protest when an animal is slaughtered for food and will probably go home and order their Mexican cook to serve up steaks for dinner. Hypocrites. They disgust me.

As someone who grew up now and again working in the fields and on ranches, I had nothing but respect for the tenacious spirit depicted in Drought. Perseverance and humor furthers. González crafts a simple but effective alignment between the coming of the rain and the birth of new children. Winner: Best Documentary, Los Angeles Film Festival. IMDb. Facebook.

Elevated genre maintains philosophical heights in first-time Spanish director Jorge Torregrossa's The End (Fin, 2012), which takes all the bite out of the ubiquitous zombie apocalypse to present more of a fade-out, as stars begin to blink out of the sky, and people disappear one by one from one second to the next, for no known cause or reason. By avoiding any evident external threat as explanation, the situation gains gravity and depth, becoming—as the program capsule attests—"a thoughtful meditation on human connectedness and individual identity." It's always lovely to watch Maribel Verdú, no less here than in her other appearance at PSIFF as the wicked stepmother in Blancanieves, and a good looking cast makes all the more poignant their disappearances one by one. Official site [Spanish]. IMDb. Wikipedia.

I was a great fan of Peter Brosens and Jessica Woodworth's Altiplano (2009) a few years back; it made my top ten list for that year. So I was excited to see their follow-up The Fifth Season (La cinquième saison, 2012), billed as a kind of sci-fi fable about—not so much man against nature (as in The Deep) but nature against man—thus, imagine my disappointment at this overwrought and regrettably pretentious film. Perhaps film companion Michael Hawley described it best as disappointingly "slight." The premise was sound, and there were some impressive visuals, but I could barely get out of the theater fast enough. Perhaps I was too tired? The press notes boast a long list of "rave" reviews, which goes to show that with film criticism, the devil can indeed quote scripture...

Ryan Lattanzio wrote up first-time director / screenwriter Antonio Méndez Espaza's Here and There (Aquí y Allá, 2012) for The Evening Class—and then later in a slightly altered version for Indiewire—when he served as a student juror at Cannes. I'm grateful for his guidance. I made a point of catching the film at PSIFF and found it to be a small, simple, but enriching human tale. I overheard some folks in the audience complain that "nothing was happening", which in my mind has become a euphemism for people unwilling to settle and breathe into the circumscribed lives of the less fortunate. A lack of compassion does not good criticism make and I wish these folks with their exasperated sighs of boredom would learn to leave a theater quietly.

I was touched by how this family set out to dream even with little chance of their dreams coming true. Esparza structures an unassuming parallel narrative that speaks to how local economic pressures shape the lives of one generation after the next. Pedro (in a humble, heartfelt incarnation—I can't quite say "performance"—by Pedro De los Santos) returns home from working "allá en El Norte" to a wife who has faithfully waited for him (yet who doubts his fidelity) and two daughters who struggle to relate to their father's difficult experience. Then there's the young boy who dreams of being a break dancer and asks Pedro's guidance on how to work in the U.S. He's become infatuated with a local girl and—in one of the film's most moving sequences—forlornly asks her to wait for him until he returns. With no opportunities at hand, it's all that men can ask of those they love when they leave home to work. Official site. IMDb. Facebook.

I was quite smitten with Xavier Dolan's Laurence Anyways (2012). Dolan is not always in control of his own talent, but is becoming increasingly so with each project. What is he? All of 25? Imagine what maturity is going to bring to his filmmaking. For now, he is mature beyond his years. From the film's earliest close-ups, I started thinking about Ingmar Bergman and by film's end felt that Laurence Anyways could very well be thought of as Scenes From A Marriage for a gynandrous generation. Sygyzies have rarely been so invigorating. My understanding is that Gus Van Sant has signed on to help hammer Dolan's film into a more commercially viable vehicle—there were excesses I could easily see cut—but the basic momentum of the film, its brave core themes, its visual imagination, are knockouts. A love story for the 21st century. Official site [Canadian]. IMDb. Wikipedia.

Winner of the Lion of the Future for Best First Film at the Venice Film Festival, Ali Aydin's Mold (Küf, 2012) had its U.S. premiere at PSIFF. This slow-burning lapidary film offers the patient viewer intense embers that all but go out during its course. Basri is a 55-year-old railroad worker, widowed for 6 years, whose son has been missing for 18 years following anti-government activity during his student days in Istanbul. With his body hunched over and exhausted from walking miles of track every day, enduring ongoing grief and uncertainty, and with hardly a change in his stony facial expression, Basri embodies one of the most wretched creatures on earth through the sheer physical presence (and hangdog countenance) of Ercan Kesal, known for his work in Nuri Bilge Ceylan's films. Mold's opening interrogation sequence is hazardously static, making me want to crawl out of my skin, but then Basri's tragic loneliness takes weight in the viewer's heart, a hard and sad stone of embittered truth set amidst Murat Tuncel's remarkable cinematography. Official site [Turkish]. IMDb. Facebook.

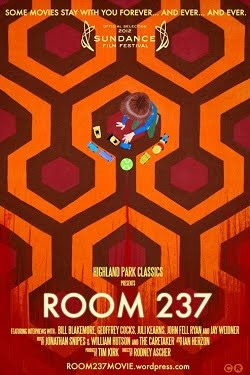

If ever you've wondered whether film critics are necessary, Rodney Ascher's Room 237 (2012) will both confirm the value of a deep critical reading of a film as well as demonstrate how some readings teeter and loop towards the ridiculous. Using Stanley Kubrick's The Shining as its fulcrum, five armchair critics pose theories about Kubrick's hidden intentions or—more pertinently—how auteurial intent can frequently have nothing to do with a spectatorial experience. You see what you want to see, perhaps even what you have to see, and whether others agree with you or laugh out loud at you, no one can take away your own experience of a film. Nor, it might be argued, should they. As much as some believe there are right and wrong opinions, or that thumbs must go up and down, Room 237 suggests that a film is not an inviolate thing; it is as malleable (and subjective) as the audience allows. See what thou wilt is the whole of the law. Official site. IMDb. Wikipedia.

Insipid musical numbers all but zap the life out of the U.S. premiere of Patrice LeConte's Suicide Shop (Le Magasin des suicides, 2012), whose characters all want to die anyways. Moments of morbid and droll brilliance coupled with enthused competent animation are not enough to save this 3D effort that explains, perhaps, why 3D is flailing at the box office. Clearly the medium has ingested the worst poison of them all: ennui. Those around me seemed more charmed by this vehicle than myself, which by film's end became disingenuous for turning its frown maniacally upside down. A bit Addams, a bit Gorey, a bit Burton, and a bit too chipper about bucking up to the depressive tendencies of the Recession. IMDb.

I was fond of Pablo Trapero's Lion's Den and Carancho, and anticipated catching White Elephant (Elefante Blanco, 2012), the third in his proposed trilogy of films chronicling social inequity. As important a subject as Trapero has tackled—that of the efficacy of the Catholic Church in mediating economic and political unrest among the disenfranchised lower classes of Argentina—the film left me curiously unengaged. I can only fault the lack of characterization of the main protagonists. It wasn't enough to have Father Nicolas (Jérémie Renier, in a Spanish-speaking role) have an illicit affair with social worker Luciana (Martina Gusmán). Renier's character, along with Gusmán's, along with Ricardo Darín's for that matter, simply never came to life as distinct personalities worthy of investment. By film's end, I felt nothing for these individuals put through their paces. The scenes of police squelching civilian unrest were unsettling but also, somehow, formulaic and offputting. IMDb. Wikipedia. Facebook [Spanish].

Post a Comment