{[[' ']]}

']]}

Another international premiere at the 15th edition of Montreal's Fantasia Film Festival currently on festival track is William Eubank's ambitious indie sci-fi drama Love (2011), produced by the alternative rock band Angels & Airwaves and poised to screen at Austin's Fantastic Fest. Slated as the opening night feature in Fantasia's Camera Lucida spotlight on "genre cinema in its utmost extreme, surprising and iconoclastic form"—Love is clearly a labor of.

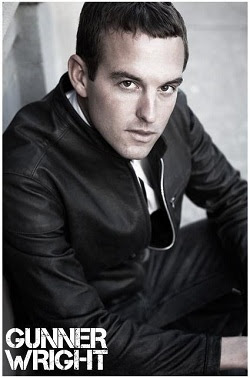

Another international premiere at the 15th edition of Montreal's Fantasia Film Festival currently on festival track is William Eubank's ambitious indie sci-fi drama Love (2011), produced by the alternative rock band Angels & Airwaves and poised to screen at Austin's Fantastic Fest. Slated as the opening night feature in Fantasia's Camera Lucida spotlight on "genre cinema in its utmost extreme, surprising and iconoclastic form"—Love is clearly a labor of.Graphing the gradual madness born from the loss of human contact and the necessity of love for the furtherance of the human spirit, if not the prolongation of the human race, Love is structured as a parallel narrative that conjures up the messenger's recitation from The Book of Job (1:15): "I alone have escaped to tell thee." The film's prologue introduces Lt. Lee Briggs (Bradley Horn) witnessing the death of his Union regiment in a violent Civil War skirmish evocatively lensed in speed ramp slow-mo. Then—as Dennis Harvey phrases it in his favorable review for Variety—the narrative "lunges nearly two centuries forward and 220 miles outward" where the routine mission of lone astronaut Lee James Miller (Gunner Wright) goes seriously awry when he loses contact with Houston HQ as the Earth self-destructs in nuclear war. It's Miller's story that makes up most of the film and Gunner Wright's performance that nearly single-handedly carries it (other than the occasional hallucinatory cameo).

"Lead thesp Wright, shouldering nearly a one-man-show burden, is gamely athletic, all-American and somewhat of a blank slate, like Kubrick's astronauts," Harvey writes, "until some unfettered personality begins to seep out." At Twitch, Kurt Halfyard agrees: "Gunner Wright is very convincing in his reaction to first loss of control, then boredom, then loneliness and despair."

"Lead thesp Wright, shouldering nearly a one-man-show burden, is gamely athletic, all-American and somewhat of a blank slate, like Kubrick's astronauts," Harvey writes, "until some unfettered personality begins to seep out." At Twitch, Kurt Halfyard agrees: "Gunner Wright is very convincing in his reaction to first loss of control, then boredom, then loneliness and despair."I caught up with Gunner Wright during Fantasia at The Irish Embassy, bought him a drink, and sat down to discuss his involvement with Eubank's respectful contribution to a lineage of thinking man's science fiction that harkens back to Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris (1972), and its more contemporary compatriot Duncan Jones' Moon (2009).

* * *

Michael Guillén: Gunner, you worked on Love for four years. For an actor, that's a considerable investment of time. How did you react when you finally saw the film projected?

Gunner Wright: I first saw Love with an audience when it premiered at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival. Although I had seen some remnants, bits and pieces, with Will, the Santa Barbara premiere was the first time I watched my performance. I was trying to watch the film for all the things we were trying to communicate and get out there, but I was being my own worst critic and looking at areas in my performance that I didn't believe—"You were real here. You were pushing it to get that emotion here"—but, that was just me from racing motorcycles for years fine tuning technique. For the most part, watching the audience get excited about the film was just special. Santa Barbara was amazing because there was so much support. It's close to L.A. and we had a lot of Hollywood there at the premiere giving us thumbs-up.

Gunner Wright: I first saw Love with an audience when it premiered at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival. Although I had seen some remnants, bits and pieces, with Will, the Santa Barbara premiere was the first time I watched my performance. I was trying to watch the film for all the things we were trying to communicate and get out there, but I was being my own worst critic and looking at areas in my performance that I didn't believe—"You were real here. You were pushing it to get that emotion here"—but, that was just me from racing motorcycles for years fine tuning technique. For the most part, watching the audience get excited about the film was just special. Santa Barbara was amazing because there was so much support. It's close to L.A. and we had a lot of Hollywood there at the premiere giving us thumbs-up.Guillén: Granted, you would be your own worst critic; but, I was impressed with the continuity of your performance. The progression of your character within such a complex narrative was noteworthy.

Wright: Thanks so much.

Guillén: As Love is a film whose narrative was built up over a long period of time, how did you adjust to that process as an actor? Were you given a general arc to your character at the beginning of filming to hold onto throughout? How did you compensate for the many adjustments made to the script over the years?

Guillén: As Love is a film whose narrative was built up over a long period of time, how did you adjust to that process as an actor? Were you given a general arc to your character at the beginning of filming to hold onto throughout? How did you compensate for the many adjustments made to the script over the years?Wright: For me, it's like asking the question: "How come kids—if you aimed a camera at my nephew or niece, let's say, when they're playing astronauts or playing Batman—deliver some of the best performances I've ever seen?" The answer: because they're in it. My nephew Jet is four and when we play Batman and Robin, I'll watch him in awe because he's in it. This aspect of filmmaking really goes back to so many moments. I could almost play you back the movie and comment, "Okay, now this scene here is being filmed at 4:00 in the morning and it's basically Will and I and we have no producers to tell us, 'Hurry up, guys.' " We're just playing like two kids in a sandbox exploring dialogue, doing some improv with random ideas that had come to him or me. In some ways you're wondering, "When is this movie going to end?" but in other areas you realize you're never going to get that opportunity again to have that much time to just play.

These moments weren't set-ups. It wasn't like Will was saying, "Instead of you being here, you go over there." It was more about getting into an emotion. A lot of those scenes had ADR or voiceover in post so I didn't really have anybody to feed off of during filming. I had a handful of moments with the actresses but most of the time I was just looking at boards, trying to pretend that I'm introducing myself to my first love. Will would feed me imaginary lines. Again, it came down to two kids with capes on.

Guillén: I appreciate that having the time to develop Love was probably a once-in-a-lifetime acting experience for you; but—now that it's finally done—do you think it's going to be a difficult movie to sell?

Guillén: I appreciate that having the time to develop Love was probably a once-in-a-lifetime acting experience for you; but—now that it's finally done—do you think it's going to be a difficult movie to sell?Wright: I do. There's a couple of great aspects to Love that are our saving grace and one of them is that one of the producers happens to be a rock star with a great fan base who love him and his projects and you see that.

Guillén: In his Variety review, Dennis Harvey noted that "marketing hook."

Wright: We were in Seattle at the E&P with 500 kids five hours before one of our shows at the Seattle International signing autographs. Ewan McGregor and all these big stars were there—my heroes, my counterparts—but because of Tom DeLonge and because of the band, Will and I and Tom and the guitar player were signing autographs for a film. It's a kind of weird aspect to the film.

Wright: We were in Seattle at the E&P with 500 kids five hours before one of our shows at the Seattle International signing autographs. Ewan McGregor and all these big stars were there—my heroes, my counterparts—but because of Tom DeLonge and because of the band, Will and I and Tom and the guitar player were signing autographs for a film. It's a kind of weird aspect to the film.Guillén: But an effective melding of art forms.

Wright: It is. The film itself is artistic. It's an arthouse film. A lot of the questions at tonight's Q&A concerned the ending. You take a young director like Will who's a great fan of Stanley Kubrick and a poetic rock and roll star like Tom and you put them together in a room and they're not necessarily going to make Iron Man 3. They might love Iron Man 3 but with their own film they want to push the envelope. They want to stretch that rubber band, so to speak.

Like I said, as an actor the toughest thing was being a lead for the first time, trying to carry a film, and learning how you do that as you go. I had to trust Will. He was my only partner in this thing. And then to place my performance in that abstract canvas. Listen, I love popcorn action shoot-'em-ups come June, July and August and what we were making with Love was foreign to me. I had to internalize a lot of the ending for myself. Where did Captain Lee Miller go? Was it heaven? Did he find a euphoria of true love? To where it's not really fair to necessarily say he went here, he went there: it's open to everyone's interpretation. And that was kind of new for me. I don't see too many films like that. It was a big risk for everybody involved.

Guillén: Most films are formulaic and manipulative. They make the audience go to a certain place. I don't believe that Kubrick wanted 2001 to be understood; he wanted it to be felt. In that respect, Will's homage to Kubrick successfully restrains itself. As Kurt Halfyard mentioned in his review at Twitch, Will doesn't embarrass himself by trying to match one of the greatest films of all time. He finds his own measure of expression.

Guillén: Most films are formulaic and manipulative. They make the audience go to a certain place. I don't believe that Kubrick wanted 2001 to be understood; he wanted it to be felt. In that respect, Will's homage to Kubrick successfully restrains itself. As Kurt Halfyard mentioned in his review at Twitch, Will doesn't embarrass himself by trying to match one of the greatest films of all time. He finds his own measure of expression.Wright: There were a handful of films that Will suggested I watch before the meat and potatoes of the space station production. One of them was, of course, 2001: A Space Odyssey and I had watched it just before he brought it up. I got on a Kubrick kick because, honestly, I was ignorant of film history. It's sad to say but true. So I watched Spartacus and a couple of other Kubrick films and I got it. I got more of a sense of why Will liked Kubrick to begin with, along with understanding other filmmakers and other actors.

I thought about what it was like to be pigeonholed in a box. I watched Cast Away and what Tom Hanks did with that character. But then you have to make it your own. That was a big issue. How insane do you take this guy? He's an astronaut. He's trained for all kinds of emergencies. You ask yourself, "What would I do if I were flying a 747 and the engine went out?" If you talk to pilots, you realize that they've been conditioned over and over and over, such that their motor skills take over in an emergency. There had to be a little bit of that with Captain Lee Miller. "Okay, I don't know what's going on but I know what I can control. And it's this button and this procedure." To where he might go off his rocker to a degree but he will still come back when his motor skills go into effect and press air and oxygen and lights are on.

I thought about what it was like to be pigeonholed in a box. I watched Cast Away and what Tom Hanks did with that character. But then you have to make it your own. That was a big issue. How insane do you take this guy? He's an astronaut. He's trained for all kinds of emergencies. You ask yourself, "What would I do if I were flying a 747 and the engine went out?" If you talk to pilots, you realize that they've been conditioned over and over and over, such that their motor skills take over in an emergency. There had to be a little bit of that with Captain Lee Miller. "Okay, I don't know what's going on but I know what I can control. And it's this button and this procedure." To where he might go off his rocker to a degree but he will still come back when his motor skills go into effect and press air and oxygen and lights are on.Guillén: This is the first performance of yours I've seen. The adage "the camera loves you" applies to you.

Wright: I appreciate that.

Guillén: Give me a sense of your training. You came out of Florida?

Wright: I raced motorcycles. My dad's in the motorcycle business and—through his business with Honda Motorcycles—the whole family got uprooted from Florida to L.A. I thought I was going to be a professional racer for the longest time and I had roads to choose and things I wanted to do that with racing, unfortunately, the more professional you are as an athlete, your world becomes two-dimensional. But because of motorcycling and other endeavors, but mainly motorcycling, everyone in Hollywood's infatuated with two wheels—that Brando, Steve McQueen, machismo kind of thing—and it's still there, even more so than when we moved to L.A. 16 years ago. So because I was a motorcycle guy, I made a lot of friends in Hollywood who wanted to hang with me and talk about bikes. But I wanted to talk about what it was like to be on a set. I had friends who were stunt doubling for actors. So I was brought into Hollywood organically and in the great way of not knowing anything about it. Not knowing if I wanted to do stunts or if I wanted to be an actor.

I met people, specifically David Barrett and his family who were huge in Hollywood. Dave's dad was Burt Reynolds' stunt double. Burt taught Dave how to swim. David was a motorcycle racer first, then did stunts in second unit, and now he's a great big producer in Hollywood. David gave me an opportunity to get on set to do some extra work and stand-in work. I had no idea what I was doing, but I really fell in love with that process. My first starts were years of extra work and stand-in work part-time here and there. Today I tell tons of actors or people in L.A. who want to get involved in acting, "You know, it sounds menial but you learn so much by being an extra." We're all extras at some point, even the stars. You're in focus and I'm in the background getting a drink? That's extra work. You're not saying anything. You're basically crossing camera. But that's how you learn the foundation, at least for me. It set the tone.

I met people, specifically David Barrett and his family who were huge in Hollywood. Dave's dad was Burt Reynolds' stunt double. Burt taught Dave how to swim. David was a motorcycle racer first, then did stunts in second unit, and now he's a great big producer in Hollywood. David gave me an opportunity to get on set to do some extra work and stand-in work. I had no idea what I was doing, but I really fell in love with that process. My first starts were years of extra work and stand-in work part-time here and there. Today I tell tons of actors or people in L.A. who want to get involved in acting, "You know, it sounds menial but you learn so much by being an extra." We're all extras at some point, even the stars. You're in focus and I'm in the background getting a drink? That's extra work. You're not saying anything. You're basically crossing camera. But that's how you learn the foundation, at least for me. It set the tone.I learned a lot of physical technique on the set of Love. There are no classes in Hollywood that teach you marks, for the most part. I took some on-camera training here and there. I had a great on-camera coach named Charles Carroll for a couple of years. Charles is great. He's a working actor, which I love. I trusted him because of that. He's working for Spielberg, and you'll see him as a judge or a lawyer, he's a big presence, and he's working, which I like.

I did a play called The Play Ground in L.A.. It was a challenging role. Very difficult. The director was a young guy out of New York City and his mentor had been Peter Flint, a great coach out of New York City, who came on his own dime to spend three weeks working with all of the cast. What helped in that theatrical experience is that The Play Ground was blocked like a feature film. It was gritty. I played a long-haired greasy pimp. It wasn't Hamlet. It was raw. And Peter was brilliant. He stripped me apart day after day. So, I did get a little bit of that formal training.

I did a play called The Play Ground in L.A.. It was a challenging role. Very difficult. The director was a young guy out of New York City and his mentor had been Peter Flint, a great coach out of New York City, who came on his own dime to spend three weeks working with all of the cast. What helped in that theatrical experience is that The Play Ground was blocked like a feature film. It was gritty. I played a long-haired greasy pimp. It wasn't Hamlet. It was raw. And Peter was brilliant. He stripped me apart day after day. So, I did get a little bit of that formal training.Guillén: How did you stumble into this project?

Wright: In a weird way I have to go back, again, to the blessings of being brought up around motorcycles. I had met Will. There was a Lifestyle pilot being shot of two motorcyclists leaving L.A. and driving up to Mendocino north of San Francisco. It was almost like a travel show with two guys on bikes going to five-star wineries and great restaurants along the way. Will's friend was putting this project together. He was the D.P., one of the shooters. It was one of those projects that never really saw the light of day, so to speak, but we had a great time. I basically rode the motorcycle, read my script on camera and hung out.

Will and I bonded enough that—when he was courted through Tom DeLonge about this project—they were thinking, "What should we do?" Angels & Airwaves had a song called "Love Like Rockets" that's about an astronaut who gets left in space. Will liked that aspect of the potential story. The more he started mulling around: "Well, who should I get to play this astronaut?", he remembered me. I got a call from Will in August 2007 saying, "Hey man, I want to talk to you about something. I don't want to talk about it over the phone. Come meet for coffee." He showed me some basic storyboards and rough sketches and—as soon as I heard the word "astronaut"—I went to eight years old in 30 seconds. I said, "Sign me up, Daddy!"

Guillén: Can you speak a bit to your specific process of creating the character of astronaut Lee Miller?

Wright: It was so far-reaching. As I said, when Will asked me about this project and mentioned, "Hey, how do you feel about playing an astronaut?", the two things that I wanted to do as a kid growing up was either race motorcycles or be an astronaut. I'm from Florida and Cape Canaveral was always just around the corner. As he was building the space station, I was trying to wrap my head around being an astronaut and doing that role justice as far as what astronauts do. All we had really were books. I'd sit on the floor and look at old photos and go through stories and try to figure out, "What would this character do on a day-to-day basis?" Other films, I would play around and watch and pick some things that I could pick apart; but, the process for creating the character in Love was abstract.

Wright: It was so far-reaching. As I said, when Will asked me about this project and mentioned, "Hey, how do you feel about playing an astronaut?", the two things that I wanted to do as a kid growing up was either race motorcycles or be an astronaut. I'm from Florida and Cape Canaveral was always just around the corner. As he was building the space station, I was trying to wrap my head around being an astronaut and doing that role justice as far as what astronauts do. All we had really were books. I'd sit on the floor and look at old photos and go through stories and try to figure out, "What would this character do on a day-to-day basis?" Other films, I would play around and watch and pick some things that I could pick apart; but, the process for creating the character in Love was abstract.Will didn't want this character to be too Cast Away, which—as I mentioned earlier—I did watch early on. I had to think about how insane was this guy going to be? How crazy was he going to be? But I kept going back to the fact that—though he might not be a Navy S.E.A.L.; he might not be a special forces operative—but, he's someone who's trained to handle a lot of different circumstances and he has a job to do to survive. He's a survivalist. And yet he's by himself for years, which—hence the title of the film—we all want contact. We all want some form of communication. That's why he breaks down when he can't see his brother's video anymore. That was his only human connection. Now all he has left are Polaroids of girls because, c'mon, this guy had at least a couple of girlfriends on Earth. [Grins.] So that was kind of the process. It was very organic. His character wasn't ever set. We really did explore and discover, sometimes even on the day.

I have to give Will tons of props as a filmmaker and as a friend, but the thing I kept thinking about when I watched the film with the audience earlier tonight that hit me as an actor was that the biggest aspect between a filmmaker and an actor together is trust. I was watching certain scenes that we started to shoot in September 2007. At that time I knew Will briefly, but I didn't know Will. You have to understand, I was in short shorts, which I didn't want to be in. I had this whole idea in my mind that I'd be wearing these cool spacesuits and he handed me these shorts and said, "Here you go, bro." It was a challenge enough to be carrying a film in my first leading man role, but to trust Will when I was in such a vulnerable situation as a first-time actor in those situations took a lot of trust. Will and I developed over the course of those four years mutual respect, mutual trust, even as friends. And tonight as I was watching the film, I noticed towards the end certain scenes where Will said, "You say what you want, man, because I know exactly where this is going to go." So I gave him everything I had. I wasn't going to second guess him. I knew his vision and I was in.

I have to give Will tons of props as a filmmaker and as a friend, but the thing I kept thinking about when I watched the film with the audience earlier tonight that hit me as an actor was that the biggest aspect between a filmmaker and an actor together is trust. I was watching certain scenes that we started to shoot in September 2007. At that time I knew Will briefly, but I didn't know Will. You have to understand, I was in short shorts, which I didn't want to be in. I had this whole idea in my mind that I'd be wearing these cool spacesuits and he handed me these shorts and said, "Here you go, bro." It was a challenge enough to be carrying a film in my first leading man role, but to trust Will when I was in such a vulnerable situation as a first-time actor in those situations took a lot of trust. Will and I developed over the course of those four years mutual respect, mutual trust, even as friends. And tonight as I was watching the film, I noticed towards the end certain scenes where Will said, "You say what you want, man, because I know exactly where this is going to go." So I gave him everything I had. I wasn't going to second guess him. I knew his vision and I was in.Guillén: Did you know, however, when you agreed to this project that it would be such a prolonged effort? Yet you remained committed enough to sandwich your participation in between whatever else you had to do to pay bills?

Wright: Absolutely. All of us did. Will would have to go off to do some DP work. Sometimes we'd have to reschedule things because at the last minute a very key person for that day had to go shoot something to earn a living. It was very cowboys and Indians style, you know? Just roll camera and shoot when you can. But I was committed, yeah.

After the first year, the project kept building momentum because the few money men that were seeing more dailies and hearing more buzz, the fans hearing more or finding behind-the-scenes photos on Facebook or Twitter or the A&A website, you kept feeling the energy and the excitement of what could be. Not what it was going to be but what it could be. We wanted it to be what everyone was hoping it would be because we were all doing it out of the honesty and the innocence of what we loved to do. I love acting. I don't want to direct. I don't want to produce. I don't want to write. I just want to act. If some of those other things come together, that's fine, but I love acting. I'll never grasp it. I'll never own the craft.

Guillén: Why would you say that? You do own your craft. You show that in this film.

Guillén: Why would you say that? You do own your craft. You show that in this film.Wright: And I appreciate that—that really means so much to me—but there are so many actors I could watch for days that resonate for me. Paul Newman. Clint Eastwood. Guys that time and time again prove themselves. It goes back to the sport of motorcycle racing for me. The most consistent driver wins the championship, not necessarily the fastest guy or the guy who wins the most races. It's the consistency and longevity of one's career that's so romantic to me.

To parlay that into golf, you can have two or three great holes and you go, "I got it. I just parred. I got it." And then the very next hole you shake it, it hits the house, and you think, "What did I just do?" There's moments when you're on set and you feel like you're an Oscar®-contending actor. "Yup! Got it!" And the very next take for me personally, I go, "Man, what in the hell am I doing?" You feel like you just lost all of that magic and skill that you had during the last take or the last scene.

Guillén: Aside from the spirit of play—which you've been describing quite affectionately in our conversation—what have you gained from this experience that has given you a professional edge or personal growth?

Wright: Two things. One, instinct. Instinct as an actor. So many times there are certain things that I will do that, again, stem from racing motorcycles. You start off analyzing the track, analyzing your moves, looking to see obstacles, and it's the same as trying to look at a scene for the day, and trying to visualize it in your mind. But sometimes the best scenes are when you throw that all away. You always hear that story, you know, where you learn the scene and its objective so that you can lose yourself and find something that you didn't expect to find. That instinct is something that Love helped me gain and grasp. But also, again, it's a technical aspect. The minute camera focus on your close-up. Finding the emotion and the scene's objective but making sure you're in focus and that you're hitting your marks, things that sound so elementary.

I just watched this great YouTube of Christopher Reeve in a scene of Richard Donner's Superman. It's a close-up but the behind the scene camera's wide so you get the marks where his feet are going to hit. It's take after take of him going after Gene Hackman and, I kid you not, he is nailing his marks with every single take—his toes are on the tape!—and I know how hard that is. People don't understand that he's either counting or he's so programmed that he's walking and his steps are perfect, but, he's in that scene. Picture four years of Love, mainly being the central character on set day in and day out, fast forward and you've done a handful of big films, smaller roles per se but you're playing Dwight Eisenhower and Leonardo di Caprio's right beside you and there's Clint Eastwood in the Paramount lot and the camera goes tight: being on set is an experience you can't buy and you can't replace it.

Guillén: Let's shift to these alternate performances. Clearly you secured these roles not on the laurels of this project?

Wright: That's right. It was kind of weird because—as I was struggling and in this world of Love—I was blessed to get small roles. I got a chance to play a secret service agent opposite Jonathan Pryce as President in G.I. Joe: The Rise Of Cobra (2009). It was a small two-day role that gave me the chance to experience some great moments with a guy like Jonathan Pryce. In The Losers from Warner Brothers I'm a jet pilot and it's me and Idris Elba and a few cast and crew working for Joel Silver. Working with Idris was amazing. Watching his process. Because I want to be a leading man. I want to do some action. I want to push myself in that world. So to get a chance to carry a film like Love is, in some ways, to be a paid fly on the wall. The Losers did what it did but what Garrett Warren, who's an amazing second unit stunts coordinator, was doing on set at least while I was there blew my mind. He was doing Avatar at the same time.

Guillén: I, too, romanticize the longevity of a career. And one of my favorite ways to approach movies, since I watch so many of them, is to take note of the early performances of actors when they're, as you say, paying their dues and learning their chops in small career-building performances. I project that somewhere down the line, perhaps because of your motorcycle skills, you'll do a Steve McQueen role; a remake of Le Mans (1971) perhaps?

Guillén: I, too, romanticize the longevity of a career. And one of my favorite ways to approach movies, since I watch so many of them, is to take note of the early performances of actors when they're, as you say, paying their dues and learning their chops in small career-building performances. I project that somewhere down the line, perhaps because of your motorcycle skills, you'll do a Steve McQueen role; a remake of Le Mans (1971) perhaps?Wright: I want it soooooo bad!

Guillén: [Laughs.]

Wright: I'm a great fan of Steve McQueen. It's funny. I was in London years ago and I found this Steve McQueen book in a bookstore at Heathrow coming back to L.A. I was so broke at that time. That was an early lesson in my acting career. I got involved in acting and immediately I got a hosting job on a Lifestyle motorcycle show so I was at least getting paid and I thought, "Here we go. This is easy." Until production went belly-up and I didn't get checks for a couple of months and I'm grabbing my guitar and I'm on Venice Beach Strand playing five days a week making $20 a day. I didn't want to call my dad and say, "Hey Dad, can you loan me $500" because he was like, "You're leaving what to be an actor?" It was the principle of course at that time. Anyway, I'm in London, I find this book, and I read this book on Steve McQueen. I had heard about him. I had liked him because he was a motorcycle guy. But when I read his story, that's when I started to research his catalogue.

Guillén: More appropriately, however, I could see you doing a Paul Newman biopic. Would you do that?

Wright: In a heartbeat. But I don't know if I could do him justice. A friend of mine in L.A. recently gave me a box set of McQueen films and a box set of Paul Newman films. I watched Cool Hand Luke...

Wright: In a heartbeat. But I don't know if I could do him justice. A friend of mine in L.A. recently gave me a box set of McQueen films and a box set of Paul Newman films. I watched Cool Hand Luke...Guillén: One of my favorite Newman films.

Wright: ...and I watched three or four more of his films including The Towering Inferno, which I love because it's got McQueen and Newman and you can see the nuances between the two. It seems like Newman loves dialogue, his performances are dialogue-driven, whereas McQueen hardly needs any dialogue. He's a presence. It's comforting who he is or at least who he appears to be.

Whoever plays Paul Newman, if that film ever comes to the surface, is the same person that I hope will give Steve McQueen credit. Out of anybody if you're considering who to cast in a biopic, James Franco did James Dean so much justice. James Dean wasn't easy to do. So you hope that someone like him can do a Newman or McQueen the same way.

Guillén: As you develop into an actor who handles leading roles, who would you want to be your leading lady? There's got to be at least one.

Wright: There's more than one. I'll throw in Raquel Welch just because I want to throw in Raquel Welch. There's so many, you know. Currently, I think Olivia Wilde. Her onscreen presence is striking. Natalie Portman is a feminine gem. I try not to be all male chauvinistic but it's somewhat like looking at a gallery of wonderful art or a museum exhibit of 30 motorcycles and each one has their own distinct beauty.

Guillén: Finally, returning to Love, can you give me a sense of how the film will roll out?

Wright: Right now Fathom Events has it in close to 500 theaters on August 10. It's live so it's 9:30 East Coast, 6:30 West Coast. You can log onto the Fathom Events website and buy the tickets on line. A couple of kids already approached me, saying, "Hey, we're going to see it in Boston."

Guillén: These are some of the fans that are following you around?

Wright: Yeah, these kids drove from New York City. It's amazing. And that again is Tom. That's not me or Will. It's the band's fans wanting to support the film and see it succeed, which is so rare for an indie film. But the August 10 event is amazing because I looked at the markets and they're all major. Chicago alone has 30 theaters. Almost every major city involved are going to have five or six theaters involved.

Guillén: What will your participation be in that event?

Wright: I don't know for certain. On the way flying here Will said the event will be three hours and will include the movie, a Q&A, and then the band at one of those venues is going to put on a psuedo-concert, an acoustic performance or something to give the fans a treat. Because it's live for that one night, every single viewer's going to see the film with a little bit something special at the end. I'm excited. I was talking to one of the other filmmakers this weekend who had heard remnants about this event, though not in detail. It's such a unique event. It could screen for more days, depending on what markets sell out down the road; but, for the fans, this is it. They have one night. This is the time. You don't have a chance to say, "Awww, I'll see it on Saturday or I'll see it at a matinee."

Guillén: There's no doubt in my mind that the value added at such cinema events is what is helping keep film culture alive. So to finish up here, Gunner, congratulations on your lead performance in Love. I wish the film well. Thank you for taking the time to talk with me today.

Wright: Hey listen, thank you, man. You're a film connoisseur yourself who's clearly been around a lot of movies, a lot of actors, and it's clear you love it. That's what I like most: just sitting around, having a drink, shooting the shit and talking about our favorite pics.

Love - William Eubank - Trailer n°1 (HD) by 6ne_Web

Post a Comment