{[[' ']]}

']]}

Chris Fujiwara is a writer, film critic, journalist, and editor. He is the author of Jerry Lewis (University of Illinois Press, 2009), The World and Its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger (Faber & Faber, 2007) and Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000) and the editor of Defining Moments in Movies (Cassell, 2007) and Peter Watkins (Jeonju International Film Festival, 2008). He is also the editor of Undercurrent, FIPRESCI's bimonthly publication.

Chris Fujiwara is a writer, film critic, journalist, and editor. He is the author of Jerry Lewis (University of Illinois Press, 2009), The World and Its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger (Faber & Faber, 2007) and Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000) and the editor of Defining Moments in Movies (Cassell, 2007) and Peter Watkins (Jeonju International Film Festival, 2008). He is also the editor of Undercurrent, FIPRESCI's bimonthly publication.* * *

Michael Guillén: I've been wandering around Insane Mute and—as in past purviews—am impressed with the topical breadth of your writings. Your rich exploration of genres and national cinemas, the global reach of your festival reports, and your select appreciation of actors is compelling; but, without question, your sampling of essays on directors and their films—ranging alphabetically from Pedro Almodóvar to Zhang Yimou—far outweighs those previous categories. For someone who is such an accomplished, articulate and poetic critic, why the site name Insane Mute? Where does that come from?

Michael Guillén: I've been wandering around Insane Mute and—as in past purviews—am impressed with the topical breadth of your writings. Your rich exploration of genres and national cinemas, the global reach of your festival reports, and your select appreciation of actors is compelling; but, without question, your sampling of essays on directors and their films—ranging alphabetically from Pedro Almodóvar to Zhang Yimou—far outweighs those previous categories. For someone who is such an accomplished, articulate and poetic critic, why the site name Insane Mute? Where does that come from?Chris Fujiwara: First of all, you are way too kind. Anyway, "insane mute" comes from a line near the end of Samuel Fuller's Shock Corridor (1963): "What a tragedy. An insane mute will win the Pulitzer Prize." I use that as a name for the site because I like it, and partly in tribute to Fuller. But it's misleading in several ways (and I don't know if that makes it better or worse as a title). Not just anyone can go insane, for one thing. For another, I'm not, strictly speaking, mute. And I don't expect to ever win the Pulitzer Prize.

Guillén: Ah yes, now I see it in the graphics between your site's banner and the film's movie poster. As you have written on so many directors, would it be a mistake to presume your cinephilic sensibility is essentially auteurist?

Guillén: Ah yes, now I see it in the graphics between your site's banner and the film's movie poster. As you have written on so many directors, would it be a mistake to presume your cinephilic sensibility is essentially auteurist?Fujiwara: Considering that the three books I've written are studies of Jacques Tourneur, Otto Preminger, and Jerry Lewis, all of whom are directors, and considering the place each of those people has had in the history of what's called auteurism, I think it's pretty clear that that would not be a mistake.

Guillén: With my batting average lately, I'm double-checking everything! How has an auteurist focus shaped your film writing? As craft, can you opine on the value of the auteurist approach? How has it helped you winnow insight from film? Have you been affected by recent shifts towards increased acknowledgment of the co-auteurial or varying sources of authorship, not just directorial? For example, the producer as auteur (Val Lewton), the screenwriter as auteur (Paul Schrader), or the cinematographer as auteur (John Alton; John F. Seitz)?

Fujiwara: To me, auteurism is not a big deal. It's not a big deal in France, either. I mean, French critics just don't discuss it. They start from the assumption that The Grissom Gang (1971) is a film by Robert Aldrich or Je rentre à la maison (2001) is a film by Manoel de Oliveira or whatever, and they just write. If they want to mention other films by the same director, to discuss certain similarities, certain differences, or a certain practice or style of directorial writing, then they do that and it's no problem. If you're studying—I don't know—Henry James' novel The Wings of the Dove, you have a text and you have, if you like, an author. You can choose to deal with the author or not. It's the same with writing about films.

Fujiwara: To me, auteurism is not a big deal. It's not a big deal in France, either. I mean, French critics just don't discuss it. They start from the assumption that The Grissom Gang (1971) is a film by Robert Aldrich or Je rentre à la maison (2001) is a film by Manoel de Oliveira or whatever, and they just write. If they want to mention other films by the same director, to discuss certain similarities, certain differences, or a certain practice or style of directorial writing, then they do that and it's no problem. If you're studying—I don't know—Henry James' novel The Wings of the Dove, you have a text and you have, if you like, an author. You can choose to deal with the author or not. It's the same with writing about films.Auteurism doesn't mean anything except taking the position that the direction of a film is a form of authorship. That doesn't mean that there's nothing problematic about the notion of authorship, as everybody knows because everybody's read Foucault. And it also doesn't mean that—in the case of a Hollywood studio system director like Jacques Tourneur—it's inappropriate to point out that there were producers, that there was such a thing as the Production Code, etc. In other words, there were other factors besides the director shaping the film. All this is obvious, and the arguments are well known.

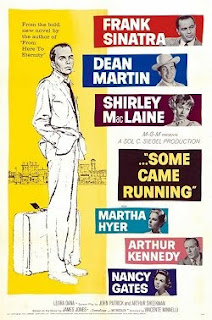

Since you asked about how auteurism has helped me, I'll say it was absolutely necessary for me to discover film in that way, through directors. Before discovering that there are directors, you discover the image and the sound, and that discovery is the primordial one. But when we realize that there is such a thing as a director, it's only at that moment that it becomes possible to talk about a film in the way that I like to talk about it. Howard Hawks and Don Siegel were, I think, probably the first directors I was aware of, but the classic example would be somebody like Vincente Minnelli. There are any number of ways of approaching, say, The Band Wagon (1953) or Some Came Running (1958) without even mentioning the director. You could talk about cultural things, or genre, or whatever. Or you could talk about the director in terms of the production history of the film, where he has a certain role that is important, but one that is also historically defined and limited by conditions. But when it comes to looking at what the film is actually doing in terms of movement, color, set design, cutting, how all these elements are working to give the film a kind of body and a kind of memory, this for me is an auteurist approach. And that's true even if we don't ever mention the name Minnelli, even if we choose the rhetorical device of saying that the film is doing things all by itself. Looking at the film as an art piece of some kind, or as a form of thought, rather than as something that is externally conditioned and determined, is to look at it in an auteurist way.

Since you asked about how auteurism has helped me, I'll say it was absolutely necessary for me to discover film in that way, through directors. Before discovering that there are directors, you discover the image and the sound, and that discovery is the primordial one. But when we realize that there is such a thing as a director, it's only at that moment that it becomes possible to talk about a film in the way that I like to talk about it. Howard Hawks and Don Siegel were, I think, probably the first directors I was aware of, but the classic example would be somebody like Vincente Minnelli. There are any number of ways of approaching, say, The Band Wagon (1953) or Some Came Running (1958) without even mentioning the director. You could talk about cultural things, or genre, or whatever. Or you could talk about the director in terms of the production history of the film, where he has a certain role that is important, but one that is also historically defined and limited by conditions. But when it comes to looking at what the film is actually doing in terms of movement, color, set design, cutting, how all these elements are working to give the film a kind of body and a kind of memory, this for me is an auteurist approach. And that's true even if we don't ever mention the name Minnelli, even if we choose the rhetorical device of saying that the film is doing things all by itself. Looking at the film as an art piece of some kind, or as a form of thought, rather than as something that is externally conditioned and determined, is to look at it in an auteurist way.Of course it's legitimate to talk about the work of Lewton, Alton, and Seitz, or Schrader as a writer, and to build up some kind of auteurist discourse around such figures who aren't functioning as directors, but who are responsible for something in the film. It could be an actor, a composer. But if John Alton's contribution is the most interesting thing in a film, then it must be a pretty minor film; a film without a director. If the film was directed by Anthony Mann or Vincente Minnelli and Alton was the cinematographer, then we may notice Alton's signature and be pleased by it, but the film is significant for reasons that go beyond Alton.

Guillén: My own site The Evening Class is named after Ousmane Sembène's frequent assertion that in Africa—though I apply this generally—cinema is the evening class for discriminating adults. In your review of Sembène's Moolaadé for the Boston Phoenix, you assert that "Moolaadé is a model of lucid, cogent, and gripping political filmmaking" and reference Sembène's poetic skill in conjoining ideas through an elegant narrative "as in a dream that feels real." And you cogently assess: "Restrained and precise camera movements; imaginative use of music; a narrative progression both ritualized and plausible; a thoughtful use of cutaways, in scenes of crisis, to integrate and implicate onlookers—all these aspects of Moolaadé reveal Sembène's mastery. If the film seems straightforward, that's because its complex design is, at every moment, the simplest possible pattern for the vision of time, space, history, and action that Sembène seeks to express." I couldn't agree more and I couldn't have phrased it better.

Guillén: My own site The Evening Class is named after Ousmane Sembène's frequent assertion that in Africa—though I apply this generally—cinema is the evening class for discriminating adults. In your review of Sembène's Moolaadé for the Boston Phoenix, you assert that "Moolaadé is a model of lucid, cogent, and gripping political filmmaking" and reference Sembène's poetic skill in conjoining ideas through an elegant narrative "as in a dream that feels real." And you cogently assess: "Restrained and precise camera movements; imaginative use of music; a narrative progression both ritualized and plausible; a thoughtful use of cutaways, in scenes of crisis, to integrate and implicate onlookers—all these aspects of Moolaadé reveal Sembène's mastery. If the film seems straightforward, that's because its complex design is, at every moment, the simplest possible pattern for the vision of time, space, history, and action that Sembène seeks to express." I couldn't agree more and I couldn't have phrased it better.As someone who understands cinema best through dialogue with directors, one of my main regrets is not having interviewed Sembène. I'm curious if you ever met him? If so, what your impressions were?

Fujiwara: I met Sembène briefly once when he came to Harvard to speak before a film. He was a tremendously impressive person, carried himself very erect, obviously very intelligent. He was rather young-looking though he was then, I guess, in his late seventies or eighties. He seemed like a person who wasn't going to take any nonsense.

Guillén: Have you written elsewhere on him? Insane Mute has only the Moolaadé review.

Guillén: Have you written elsewhere on him? Insane Mute has only the Moolaadé review.Fujiwara: No, unfortunately, but I would like to.

Guillén: Which leads me to ask, how you go about deciding which film to finesse out of a director's body of work? Is this choice, chance or assignment?

Fujiwara: Many of the pieces that are linked through my site are things that I wrote on assignment, especially for the Boston Phoenix. Some of them were assignments I asked for; others were things I was asked to do.

Guillén: You have addressed several national cinemas in your writings but I would like to draw attention to cinema from the Global South, especially Africa, which are given short shrift in both critical analysis and distribution/exhibition. Were it not for the traveling arm of New York's African Film Festival, would North American audiences even see these films? Their presence on the international film scene articulates political strategies of survival, defiance and solidarity. As Sembène has himself said: "Culture is political, but it's another type of politics. In art, you are political, but you say, 'We are' and not 'I am.' "

I'm grateful for the report of your "ambiguous adventures" at the 2003 African Film Festival and how you culled out the sea's primacy in that year's predominant focus on films from coastal West Africa. You intuited the sea's "complex role in the African cinematic imagination: it's a nurturing and destructive spirit, an image of beauty and death, and a route of invasion or escape." I love how you quipped, "Among women's-prison musicals, Karmen Geï (2001) has no trouble surpassing Chicago (2002)" and was thrilled by your suggestion that Karmen Geï attempts to "Africanize blaxploitation"! Which leads me to ask about the conversation over time and space between disparate films. Can you speak to the value of understanding films through each other and in dialogue with each other and—as in your example of Africanizing blaxploitation—across genres?

I'm grateful for the report of your "ambiguous adventures" at the 2003 African Film Festival and how you culled out the sea's primacy in that year's predominant focus on films from coastal West Africa. You intuited the sea's "complex role in the African cinematic imagination: it's a nurturing and destructive spirit, an image of beauty and death, and a route of invasion or escape." I love how you quipped, "Among women's-prison musicals, Karmen Geï (2001) has no trouble surpassing Chicago (2002)" and was thrilled by your suggestion that Karmen Geï attempts to "Africanize blaxploitation"! Which leads me to ask about the conversation over time and space between disparate films. Can you speak to the value of understanding films through each other and in dialogue with each other and—as in your example of Africanizing blaxploitation—across genres?Fujiwara: I'm very interested in this whole subject you raise of establishing links across generic, chronological, geographical, or national boundaries. It's one of the main things a writer does, isn't it? You have to let yourself be aware of connections and not repress the feeling that a connection might exist, even if it seems unlikely or tenuous or purely subjective.

Some films sort of demand to be seen in dialogue with other films. For example, any film based on Carmen, as Karmen Geï was, is automatically entering into such a dialogue. With other films, it's often the writer, the critic, who is creating the dialogue. I recently wrote about Pedro Costa's Ne change rien (2009) that when Jeanne Balibar quotes the phrase "Amuse-toi"—meaning "have fun", which is something people say to actors during film shoots—I realized for the first time that in Gus Van Sant's Elephant when one of the killers says to the other, "Above all, have fun," it could be understood as a reference to cinema. I mean, to me, this is valid. Maybe it's interesting to the reader or not; but, it struck me so I assume it would strike other people. Obviously I don't put it in the piece because I think it says something important about Ne change rien, but more because it's—like you say—extending the conversation over time and space.

Some films sort of demand to be seen in dialogue with other films. For example, any film based on Carmen, as Karmen Geï was, is automatically entering into such a dialogue. With other films, it's often the writer, the critic, who is creating the dialogue. I recently wrote about Pedro Costa's Ne change rien (2009) that when Jeanne Balibar quotes the phrase "Amuse-toi"—meaning "have fun", which is something people say to actors during film shoots—I realized for the first time that in Gus Van Sant's Elephant when one of the killers says to the other, "Above all, have fun," it could be understood as a reference to cinema. I mean, to me, this is valid. Maybe it's interesting to the reader or not; but, it struck me so I assume it would strike other people. Obviously I don't put it in the piece because I think it says something important about Ne change rien, but more because it's—like you say—extending the conversation over time and space. Guillén: I deeply admire and respect your appreciation of genre. In my recent conversation with Elliott Lavine, we approached the juiciness of genre and the importance of its emotional communication to audiences, as well as its often maligned status among film academicians who consider themselves intellectually above genre's visceral impact. Your appreciation, however, is dazzlingly eclectic: you've written on horror (the giallo nightmares of Mario Bava, Mario Caiano and Antonio Margheriti; the zombie politics of George Romero's Land of the Dead), fantasy/science fiction (Kurt Neumann's 1958 The Fly, Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight, Steven Soderbergh's Solaris, even a stern chastisement of the robots on MST3K!), martial arts, industrial films (are they a genre?), melodramas (Douglas Sirk), sword and sandal epics, westerns (Jacques Tourneur's Stranger On Horseback) and most notably film noir and crime dramas, which is the genre I'd like to explore with you today. But first, how important is it for cinephiles to keep in touch with contemporary trends in genre? And how much is an appreciation of genre determined by the diversity of personal taste?

Guillén: I deeply admire and respect your appreciation of genre. In my recent conversation with Elliott Lavine, we approached the juiciness of genre and the importance of its emotional communication to audiences, as well as its often maligned status among film academicians who consider themselves intellectually above genre's visceral impact. Your appreciation, however, is dazzlingly eclectic: you've written on horror (the giallo nightmares of Mario Bava, Mario Caiano and Antonio Margheriti; the zombie politics of George Romero's Land of the Dead), fantasy/science fiction (Kurt Neumann's 1958 The Fly, Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight, Steven Soderbergh's Solaris, even a stern chastisement of the robots on MST3K!), martial arts, industrial films (are they a genre?), melodramas (Douglas Sirk), sword and sandal epics, westerns (Jacques Tourneur's Stranger On Horseback) and most notably film noir and crime dramas, which is the genre I'd like to explore with you today. But first, how important is it for cinephiles to keep in touch with contemporary trends in genre? And how much is an appreciation of genre determined by the diversity of personal taste?Fujiwara: I guess it's an academic, professional, or fan-orientation thing, so if you're in one of those groups, you'll feel compelled to keep up with your chosen genre, and if you're not, you'll have more of an optional, haphazard relationship to it.

Guillén: You might recall that I approached you a few years back in appreciation of your participation in a fascinating interview on "Crime and the American genre film" in which Kinugasa intriguingly proposed: "The thief has been a central figure in films about crime, in the American genre film, and in film noir. In a sense, there is also a link between the idea of the genre film and theft, for insofar as it's a repetition of certain patterns and characters, the genre film is the result of quoting or even stealing elements from previous films." The San Francisco Bay Area, as you might know, is steeped in film noir, what with Elliott's programming efforts at the Roxie Film Center, Eddie Muller's Noir City Film Festival, and Steve Seid's brave explorations of pulp cinema for the Pacific Film Archive.

Guillén: You might recall that I approached you a few years back in appreciation of your participation in a fascinating interview on "Crime and the American genre film" in which Kinugasa intriguingly proposed: "The thief has been a central figure in films about crime, in the American genre film, and in film noir. In a sense, there is also a link between the idea of the genre film and theft, for insofar as it's a repetition of certain patterns and characters, the genre film is the result of quoting or even stealing elements from previous films." The San Francisco Bay Area, as you might know, is steeped in film noir, what with Elliott's programming efforts at the Roxie Film Center, Eddie Muller's Noir City Film Festival, and Steve Seid's brave explorations of pulp cinema for the Pacific Film Archive.I'd like to address first of all Elliott's disturbing observation that in recent years audiences resist giving credit to film being a powerful medium and try, instead, to exert power over the medium rather than allowing themselves to be—as Susan Sontag phrased it sitting in the third row mid-center—"kidnapped" by the images projected on the screen. Have you observed anything similar?

Fujiwara: Yes, and this is exactly what I wrote about so many years ago in that MST3K article you mentioned.

Guillén: Do you think such resistance might be attributable to DVD cinephilia and increasing trends towards streaming microcinema where the image is smaller and, thus, more easily overpowered? Let alone the false sense of sovereignty that the remote control affords?

Fujiwara: Undoubtedly. For me the most important differences between film and video aren't so much in resolution, but more in the size of the screen, the placement of the viewer, and the ability to control the time, the rate, and the order of viewing, all of which implies a change in the position of the viewer relative to the film. I don't want to say this is all bad or all good. I mean, the benefits are obvious, but so I think is the downside. I talked about this a little in an article "Cinephilia and the Imagination of Filmmaking" that I wrote for Framework's Cinephilia Dossier: What Is Being Fought For By Today's Cinephilia(s).

Fujiwara: Undoubtedly. For me the most important differences between film and video aren't so much in resolution, but more in the size of the screen, the placement of the viewer, and the ability to control the time, the rate, and the order of viewing, all of which implies a change in the position of the viewer relative to the film. I don't want to say this is all bad or all good. I mean, the benefits are obvious, but so I think is the downside. I talked about this a little in an article "Cinephilia and the Imagination of Filmmaking" that I wrote for Framework's Cinephilia Dossier: What Is Being Fought For By Today's Cinephilia(s).Guillén: This is undoubtedly a gross generalization, but, why do you think academics—in contrast to populist audiences, let's say—are afraid to be entertained? Is entertainment subversive to academic imperatives?

Fujiwara: No, I don't think so at all. If anything, it's the reverse. Academia seems to be trying to change itself into a form of entertainment. Actually I think academics love to be entertained as much as anybody else, and many of them are invested in justifying their pleasure, or the things they take pleasure in, as relevant to their field of scholarship.

Guillén: You've tantalizingly touched upon this in your review of Antonio Margheriti's Castle of Blood (Danza macabra, 1964), wherein you've stated: "What happens when a film entertains us? Perhaps by being entertained we fulfill a contract we've entered into with the film. Perhaps we approve of the story it tells because it's one we already know. Or perhaps it's just that we make it to the end." You add that Castle of Blood is "impressive as an object lesson in cinema. It stages the longing for diversion, the viewer's estrangement from the present, and the disillusionment that comes when the diversion is no longer diverting."

Guillén: You've tantalizingly touched upon this in your review of Antonio Margheriti's Castle of Blood (Danza macabra, 1964), wherein you've stated: "What happens when a film entertains us? Perhaps by being entertained we fulfill a contract we've entered into with the film. Perhaps we approve of the story it tells because it's one we already know. Or perhaps it's just that we make it to the end." You add that Castle of Blood is "impressive as an object lesson in cinema. It stages the longing for diversion, the viewer's estrangement from the present, and the disillusionment that comes when the diversion is no longer diverting."Fujiwara: What I was trying to say in that piece on Margheriti—and I've since expanded that for an anthology on Italian horror that's being published in France this year—is that there is a certain way of doing genre movies where things are pushed so far that a criticism of the genre, and of the audience, and even maybe of the whole institution of cinema, becomes evident. I'm not interested primarily in any genre as such, or for itself, but I'm very interested in genre undoing itself. The importance of genre is that there is a communication with the audience. Without that you can't get to any kind of real critique of the audience that would be valid. Directors like Margheriti, and especially Mario Bava, are important to me because they make films for pleasure, for their own pleasure and for the pleasure of the audience, which also happen to be—maybe not attacks on pleasure—but films that in a powerful way reveal how pleasure is constructed and that try to expose something about the costs of pleasure. Danza macabra (Castle of Blood) is a very good example of this, and so is Apocalypse domani (Cannibal Apocalypse, 1980), to name another Margheriti film.

Guillén: You've argued that "film noir" is a marketing buzz phrase that assisted repertory programming in the '60s and '70s but that, otherwise, you don't really know what it is. You've even called for a moratorium on the usage of the term "film noir" to describe films that you suggest are more accurately crime dramas or thrillers. What are your thoughts on Elliot's effort to break out of the definitional grip of film noir as a genre in order to appreciate noir stylism in films that fall outside of systems of film noir classification?

Fujiwara: I think it's great. It's good programming. Any way you can get House of Horrors onto a screen, you should do it. I love what Elliot says about genre. I think he's absolutely right about the emotional element and the element of pleasure, the unashamed (or maybe even a little ashamed—to give it an extra kick) promotion of pleasure in genre film. There is a great book that I'm pretty sure is out of print and that not enough people know about called Kings of the Bs: Working Within the Hollywood System—An Anthology of Film History and Criticism, edited by Todd McCarthy and Charles Flynn, which came out in the 1970s. It's a thick book with a mix of scholarly articles, historical articles, pieces on individual films, and interviews. Everyone interested in film should read the book and watch the films that are discussed in it, not just the films by Robert Siodmak and Edgar G. Ulmer and Joseph H. Lewis and Roger Corman, but Sam Katzman productions directed by Fred F. Sears, down to Russ Meyer and further down to Herschell Gordon Lewis. I don't put Meyer and Lewis lower as artists; I'm referring to a hierarchy of respectability. There's a great essay by Richard Thompson on Thunder Road (1958) in that book that articulates the point of view that Elliot is also speaking for.

Fujiwara: I think it's great. It's good programming. Any way you can get House of Horrors onto a screen, you should do it. I love what Elliot says about genre. I think he's absolutely right about the emotional element and the element of pleasure, the unashamed (or maybe even a little ashamed—to give it an extra kick) promotion of pleasure in genre film. There is a great book that I'm pretty sure is out of print and that not enough people know about called Kings of the Bs: Working Within the Hollywood System—An Anthology of Film History and Criticism, edited by Todd McCarthy and Charles Flynn, which came out in the 1970s. It's a thick book with a mix of scholarly articles, historical articles, pieces on individual films, and interviews. Everyone interested in film should read the book and watch the films that are discussed in it, not just the films by Robert Siodmak and Edgar G. Ulmer and Joseph H. Lewis and Roger Corman, but Sam Katzman productions directed by Fred F. Sears, down to Russ Meyer and further down to Herschell Gordon Lewis. I don't put Meyer and Lewis lower as artists; I'm referring to a hierarchy of respectability. There's a great essay by Richard Thompson on Thunder Road (1958) in that book that articulates the point of view that Elliot is also speaking for. Guillén: Returning to Kinugasa's theft hypothesis that there is a link between the idea of the genre film and theft, insofar as it repeats certain patterns and characters and is the result of quoting or even stealing elements from previous films, I am reminded of the Paul Schrader films which Elliot has programmed in his Not Necessarily Noir series. In your write-up of the Schrader retrospective held at Harvard Film Archive early last year, you declared Schrader's first directorial effort Blue Collar to be the best of his 30+-years career and that "there is something studied, unfelt, unreal" in Schrader's handling of Hardcore's potent thematic tensions. Brecht Andersch has detailed at SFMOMA's Open Space that Paul Schrader's script for Brian De Palma's Obsession borrowed its brilliant kidnap ransom-delivery device from Kurosawa's masterpiece, High and Low, which I recently caught during one of its centennial screenings. I was stunned by it. This was a Kurosawa I had never seen before and, in my estimation, the best film of his I'd ever seen. I was heartened to read you felt the same in your review.

Guillén: Returning to Kinugasa's theft hypothesis that there is a link between the idea of the genre film and theft, insofar as it repeats certain patterns and characters and is the result of quoting or even stealing elements from previous films, I am reminded of the Paul Schrader films which Elliot has programmed in his Not Necessarily Noir series. In your write-up of the Schrader retrospective held at Harvard Film Archive early last year, you declared Schrader's first directorial effort Blue Collar to be the best of his 30+-years career and that "there is something studied, unfelt, unreal" in Schrader's handling of Hardcore's potent thematic tensions. Brecht Andersch has detailed at SFMOMA's Open Space that Paul Schrader's script for Brian De Palma's Obsession borrowed its brilliant kidnap ransom-delivery device from Kurosawa's masterpiece, High and Low, which I recently caught during one of its centennial screenings. I was stunned by it. This was a Kurosawa I had never seen before and, in my estimation, the best film of his I'd ever seen. I was heartened to read you felt the same in your review. Any focus on Schrader treads on soft padded feet towards his version of Cat People (1982) based on the 1942 Val Lewton/Jacques Tourneur collaboration, which you've credited as your first Tourneur film? You have written one of the best—if not definitive—studies on the films of Tourneur, which was at my bedside for many months when I was coordinating the Val Lewton blogathon at The Evening Class. I was wholly impressed with your thoughts on The Leopard Man (1943), which was also perhaps my first exposure to screen capture analysis. You've also provided a commentary to Kevin Lee's video essay on Night of the Demon (1957). Can you comment on what it has meant for you as a critic to use screen capture analysis and video essays—the increasingly popular tools of the "new cinephilia"—to delineate the formal visual elements of film? Will these supplant print journalism? What are the pros and cons of each?

Any focus on Schrader treads on soft padded feet towards his version of Cat People (1982) based on the 1942 Val Lewton/Jacques Tourneur collaboration, which you've credited as your first Tourneur film? You have written one of the best—if not definitive—studies on the films of Tourneur, which was at my bedside for many months when I was coordinating the Val Lewton blogathon at The Evening Class. I was wholly impressed with your thoughts on The Leopard Man (1943), which was also perhaps my first exposure to screen capture analysis. You've also provided a commentary to Kevin Lee's video essay on Night of the Demon (1957). Can you comment on what it has meant for you as a critic to use screen capture analysis and video essays—the increasingly popular tools of the "new cinephilia"—to delineate the formal visual elements of film? Will these supplant print journalism? What are the pros and cons of each? Fujiwara: The Night of the Demon video essay with Kevin was an experiment; in my mind we were trying to make a little poem using some of the material of the film. Screen capture analysis is not so new because in the past people used frame blowups; it's easier and cheaper now, so it's done more often. Video essays are a great idea; Tag Gallagher has done some remarkable ones. I haven’t seen enough examples of the format to comment in general, but the potential is obviously great. My intuitive reaction is that this is a format I would use for a kind of poetic film or poetic commentary, rather than for what I would call criticism. To me it's easier and more understandable to do criticism with words on a page.

Fujiwara: The Night of the Demon video essay with Kevin was an experiment; in my mind we were trying to make a little poem using some of the material of the film. Screen capture analysis is not so new because in the past people used frame blowups; it's easier and cheaper now, so it's done more often. Video essays are a great idea; Tag Gallagher has done some remarkable ones. I haven’t seen enough examples of the format to comment in general, but the potential is obviously great. My intuitive reaction is that this is a format I would use for a kind of poetic film or poetic commentary, rather than for what I would call criticism. To me it's easier and more understandable to do criticism with words on a page. Guillén: Your conversation on Tourneur with Pedro Costa—one of my favorite interviewees and highly influential in changing my attitudes towards digital filmmaking—is an intoxicating discussion as the two of you try to piece together a portrait of Tourneur as a personal man apart from his directing. I would have loved to have been a fly on the wall for that one! Clearly, I Walked With A Zombie (1943) influenced Casa de Lava (1995), as Night of the Demon influenced Tarrafal (2007). Any insights or appreciation on how Costa has channeled Tourneur here?

Guillén: Your conversation on Tourneur with Pedro Costa—one of my favorite interviewees and highly influential in changing my attitudes towards digital filmmaking—is an intoxicating discussion as the two of you try to piece together a portrait of Tourneur as a personal man apart from his directing. I would have loved to have been a fly on the wall for that one! Clearly, I Walked With A Zombie (1943) influenced Casa de Lava (1995), as Night of the Demon influenced Tarrafal (2007). Any insights or appreciation on how Costa has channeled Tourneur here?Fujiwara: I don't really have anything to say about the way Tourneur is present in Casa de Lava and Tarrafal. It's there, it's nice, but it's not especially interesting to me, and anyway, it's been discussed a lot. Those are great films that completely transform their sources. I enjoy talking with him about Tourneur, or about anything else.

Guillén: In your Undercurrent review of the anthology On Film Festivals edited by Richard Porton you circumambulate an issue at the heart of a recent discussion at Girish Shambu's site. You write: "[W]ithin the cosmopolite contingent there is another divide just as deep, based on taste. On one side are ranged those happy few who are interested in the most 'difficult' cinephilic fare (which may include popular films of the past shown in retrospectives); on the other side, everyone else. This taste divide is never more apparent than at the closing ceremonies of certain competitive festivals that stack their juries with cinephiles: the grand prize and the audience prize almost always go to different films." More importantly, you caution against the "calcification of taste" or, perhaps even more importantly, false battles over taste. Or even worse, the cheerful abandonment of taste to guise a lack of discernment. But are you saying taste is exclusionary? Can I not enjoy Apitchatpong Weerasethakul as much as I enjoy Adam Wingard?

Guillén: In your Undercurrent review of the anthology On Film Festivals edited by Richard Porton you circumambulate an issue at the heart of a recent discussion at Girish Shambu's site. You write: "[W]ithin the cosmopolite contingent there is another divide just as deep, based on taste. On one side are ranged those happy few who are interested in the most 'difficult' cinephilic fare (which may include popular films of the past shown in retrospectives); on the other side, everyone else. This taste divide is never more apparent than at the closing ceremonies of certain competitive festivals that stack their juries with cinephiles: the grand prize and the audience prize almost always go to different films." More importantly, you caution against the "calcification of taste" or, perhaps even more importantly, false battles over taste. Or even worse, the cheerful abandonment of taste to guise a lack of discernment. But are you saying taste is exclusionary? Can I not enjoy Apitchatpong Weerasethakul as much as I enjoy Adam Wingard?Fujiwara: I don't really want to be in the position of telling people what they can and can't enjoy, which is a ridiculous thing to try to do, obviously. In my review of Richard Porton's book, I was expressing my own discomfort with the current situation with regard to taste, with regard to canons or the destruction of canons, with regard to cinephilia, this sort of live-and-let-live approach where everyone can like the films they want to like, and so you have the little clique who like Pedro Costa over here, looking down their noses at the people who like, oh, some bourgeois thing, and so forth. Now of course it's rather difficult to criticize this. There's a satisfaction that we can take now in the fact that we can see all kinds of films because of DVDs and the internet. But this also means that people are farther apart, to the point that dialogue is attenuated and instead of a film culture it looks more and more like there are only individual, disconnected film objects that people revolve around. It's already a cliché that any big-sized film festival really becomes a collection of smaller festivals happening at the same place and time and catering to different audiences. Well, what's the next step from that? Why is there a film festival if all it is, is a bunch of micro-festivals? I mean, any individual's experience of watching movies over the course of, say, a year, can be regarded as that person's own micro-festival.

That's why in that book review I suggested that there is probably an area that is in danger of being ignored in current film culture, some kind of middle area between the purely commercial and the purely cinephile. Basically I'm trying to argue that there is a dialogue that is not happening. No doubt there are good reasons why it can't happen, maybe in some cases it shouldn't happen. No one's going to bother to try to get Sarah Palin to watch Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010). But where there is a possibility of a dialogue, and the dialogue is not happening, it's destructive.

Jean-François Rauger, the programming director of the Cinémathèque française, told me recently that the Cinémathèque restored, in the same year, two films: one was a Straub-Huillet film, I think Lothringen, and the other was Mario Bava's Sei donne per l'assassino (Blood and Black Lace, 1964), and the two films were actually shown as a double bill in a series devoted to recent restorations. Double bills like that should happen all the time, there should be a way to cultivate an audience that can enjoy both Bava and Straub-Huillet. But that means, precisely, dialogue, a conversation, because you can't just show the films and expect that everyone will magically get it. Aaron Gerow said that about retrospectives, in a piece he wrote for Undercurrent: he said basically that it's great if festivals do retrospectives (and by the way too few of them do), but there really should also be a forum for discussion, for some discourse, surrounding the retrospective, a way of putting films in critical and historical context.

Jean-François Rauger, the programming director of the Cinémathèque française, told me recently that the Cinémathèque restored, in the same year, two films: one was a Straub-Huillet film, I think Lothringen, and the other was Mario Bava's Sei donne per l'assassino (Blood and Black Lace, 1964), and the two films were actually shown as a double bill in a series devoted to recent restorations. Double bills like that should happen all the time, there should be a way to cultivate an audience that can enjoy both Bava and Straub-Huillet. But that means, precisely, dialogue, a conversation, because you can't just show the films and expect that everyone will magically get it. Aaron Gerow said that about retrospectives, in a piece he wrote for Undercurrent: he said basically that it's great if festivals do retrospectives (and by the way too few of them do), but there really should also be a forum for discussion, for some discourse, surrounding the retrospective, a way of putting films in critical and historical context.Guillén: Oh my gosh! You have just created a pearl out of the very irritant that has had me on edge recently: the cliquishness that devolves from personal taste. I, too, hunger for attention on this middle area between the purely commercial and the purely cinephile.

That Sarah Palin line, by the way, is eminently quoteworthy!

Your recent N+1 essay "To Have Done with the Contemporary Cinema" really had me scratching my head so I posted a half-baked entry just to get the gears grinding, which I'm glad I did because minds much sharper than mine guided me to an understanding of your intent. My initial take was that you were bashing journalists as being slaves to the contemporary; mechanics at the heart of capitalism? "Gio Abate", however, assured me I was misunderstanding you and mischaracterizing your argument. He said that you were actually saying you missed being a journalist and having that connection (however faulty at times) to the contemporary and that academia ("for all its other potential and actual graces") insulates one from the contemporary; not necessarily a good thing. Further, Gio parsed that you're not saying the problem is with contemporary cinema but how to get a grip on the contemporary, which Zach Campbell likewise proposed saying your essay "punctured the nebulous, sometimes arrogant, and bloated connotations of the term itself." Chuck Stephens argued that digital access has provided an increased access to the contemporary. All that being said, I still have no clear definition of the "contemporary" as it applies to "contemporary cinema" and am wondering if I'm even supposed to? Perhaps "contemporary cinema" is simply that moment when the time that a spectator takes to watch a film aligns with the time within the film? Since, as you say, the contemporary can never be within the film and can only exist outside the film, wouldn't contemporaneity, then, be firmly situated in the spectatorial experience?

But my true question would be if becoming an established academic trumps the conscribed pleasures of being a journalist? For some reason I have in my mind this fantasy that you are being invited to film festivals all over the world. How can this not be the case?

Fujiwara: "To Have Done with the Contemporary Cinema" is, partly, a disguised autobiography. Maybe it should be interpreted as a plea for help. The autobiographical part is right up front in the first line, where I talk about having been a journalist, and then I write the words, "I wish I were a journalist again," which I think are unambiguous.

I'm far from being an "established academic". I've taught, and currently teach, a number of courses at various colleges and universities as an adjunct professor, and as everyone knows, to be an adjunct is to be in the Third World of academia. But I'm also not currently writing as a journalist with much frequency. I'm not closing the door on it, it's just not something I'm doing much now.

I allowed myself, in this piece, to put in some of my ambivalence about both journalism and about academia. I come right out and admit that I used to have an unwarrantedly dismissive, snobbish attitude toward the word "journalism". I don't anymore; in fact I am more than fond of at least one journalist. But there is a difference between film criticism and film journalism, and most film journalism ends up functioning, intentionally or not, as a form of publicity. Which is where the lines about capitalism and the heart machine and all that in the piece come from.

Anyway, I don't think I should go on and reinterpret my own piece. It's there, people can read it and feel how they feel about it. I want to say more about the idea of the contemporary, it's a word that has a lot in it, but that will be for another piece. In "To Have Done with the Contemporary Cinema", I'm trying to start to lay out some of the problems around the way the contemporary is understood and used as a category in the world of cinema.

Guillén: I know I certainly need some clarification on that issue so I look forward to what you discover. Notwithstanding Chuck Stephen's optimistic disposition that the contemporary has become more readily available through digital access, the evasiveness of the contemporaneous can effectively be argued through the case of José Luis Guerín, whose films have yet to be made available on Netflix. In his instance the contemporary is still—in effect—waiting to happen for many folks. This seems to resonate with your brief appreciation of the February 2008 Guerin retrospective at the Harvard University Archives, wherein you considered "the nature of cinematic time, which Guerín proves to be reversible and infinite, defeating any notional progress or goal." Perhaps the contemporary is disguised in temporal tense? It never has been and it never will be? Perhaps it reveals itself in temporal aspect? It always is? And, again, the contemporary moment is when the spectator faces that revelation?

Guillén: I know I certainly need some clarification on that issue so I look forward to what you discover. Notwithstanding Chuck Stephen's optimistic disposition that the contemporary has become more readily available through digital access, the evasiveness of the contemporaneous can effectively be argued through the case of José Luis Guerín, whose films have yet to be made available on Netflix. In his instance the contemporary is still—in effect—waiting to happen for many folks. This seems to resonate with your brief appreciation of the February 2008 Guerin retrospective at the Harvard University Archives, wherein you considered "the nature of cinematic time, which Guerín proves to be reversible and infinite, defeating any notional progress or goal." Perhaps the contemporary is disguised in temporal tense? It never has been and it never will be? Perhaps it reveals itself in temporal aspect? It always is? And, again, the contemporary moment is when the spectator faces that revelation?I'm scheduled to interview Guerín in Toronto. If I were to ask him one question on your behalf, what would it be?

Fujiwara: "What is your favorite Allan Dwan film?"

Guillén: Researching your work on the Internet, I came upon a few references to your musical involvement with a group called Cul de Sac? Can you speak to your involvement with them? I get the sense you were a lyricist, something of a poet? Much of your film writing is poetically polyvalent and open-ended (capturing two conflicting ideas within one image), is this where the poetry has gone in your writing or is there a slim volume to be hunted out somewhere?

Fujiwara: I was the bass player of Cul de Sac, which was a kind of—I don't know—art-rock, avant-rock, post-rock, whatever band (actually the term "post rock" was first used in reference to us by Simon Reynolds, so we do have our place in history). I wrote a fairly long poem which was included in the liner notes to a CD they did after I left the band. The poem includes the phrase "the frog of satisfaction", which I think may have been a reference to Mario Bava, but I can't remember. Fortunately, there is no volume of poetry by me to be hunted out anywhere.

Guillén: Chris, thank you for your generous intellect and for helping me gain a better grasp of your work. My best.

Cross-published on Twitch.

Post a Comment